|

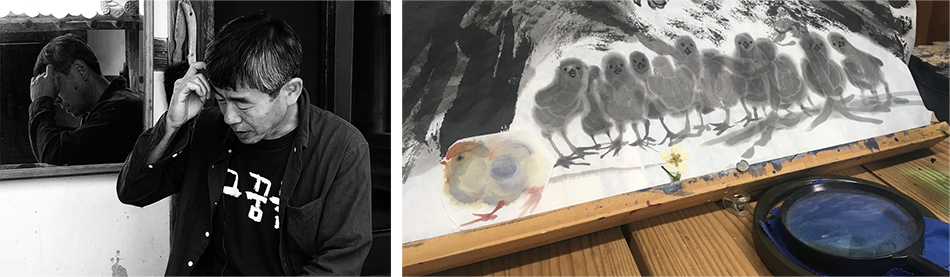

Illustrator Kim Hwan-Young

2019.07.08

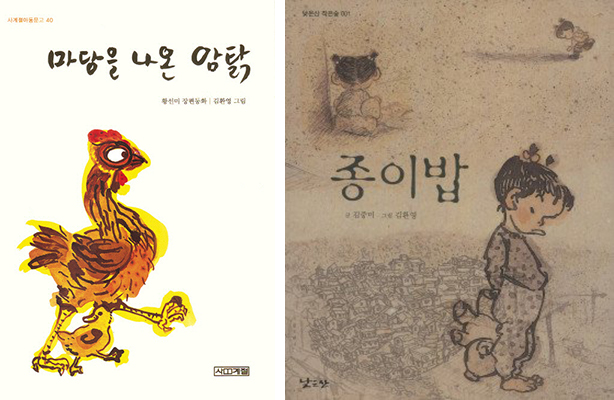

Illustrator Kim Hwan-Young has captured readers' hearts with his beautiful work in children's tales like Paper Rice (naznsan), The Hen Who Dreamed She Could Fly (Sakyejul) and The Children Who Swallowed the Sun (Changbi), as well as picture books including The Butterfly Catching Father (Gilbut Children), Corn (Sakyejul) and Bbaeddaegi (Changbi). His illustrations are known for their powerful brush strokes that can seem crude and rough at times, while his India-ink painting style conveys Korean emotions. Kim often opens up his atelier to readers, which is nestled inside a small countryside village in Boryeong, South Chungcheong Province. After leaving the city for the countryside, Kim created a studio for himself, and he has never stopped working since. In fact, he has been creating more artwork, as the artist has said his work required him to have a sincerity that could only be gained from living outside the city. The books Kim has illustrated have a quaint, countryside beauty to them, and living outside the city has only made Kim's work more plentiful and polished.

Q. Hello. It is wonderful to meet you through our webzine, K-Book Trends. Can you please introduce yourself to our readers?

A. Hello, I am Kim Hwan-Young, currently making picture books in a small city called Boryeong in South Chuncheong Province.

Q. Was there a specific reason you decided to move to the countryside?

A. I think it was the influence of fairy tale books that led me to leave the city. In fairy tale books, oftentimes you find yourself needing to draw scenes from the countryside, but I grew up in Seoul, and there were many aspects I simply wasn't aware of because I lacked that experience. Especially in the case of fairy tales written by Kwon Jung-saeng, there were many things I couldn't express because I hadn't grown up in the countryside. These things all led me here, and I think I am now 50 percent country folk.

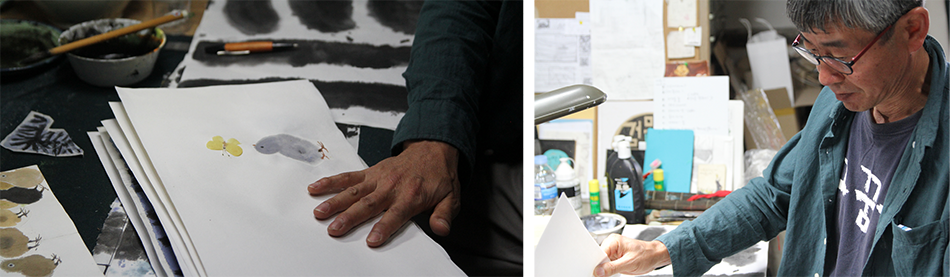

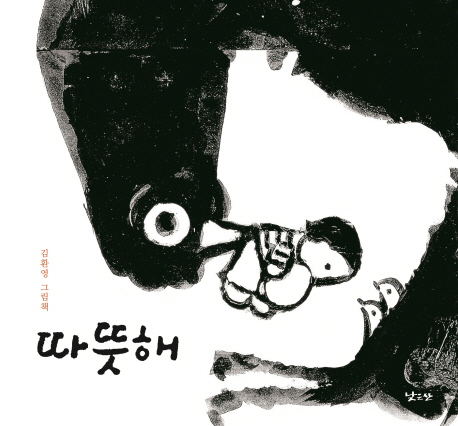

It's Warm

Q. Through your existing work like The Hen Who Dreamed She Could Fly, Paper Rice, Bbaeddaegi and Corn as well as your most recent It's Warm, you've already reached so many readers. You've left a mark on readers who enjoy your work with broad, crude brushstrokes and Korean style of illustrating. What is most important to you when you illustrate books?

A. That would be the reality of things. This refers to my current style of living, as well. Many readers refer to The Hen Who Dreamed She Could Fly as my most representative work and this I started illustrating in the city. I completed it in the countryside. I did my best when I was in Seoul, but I realized there were limits. To create paintings of rural scenery, I even resorted to carving my own brushes out of bamboo.

The Hen Who Dreamed She Could Fly, Paper Rice

Q. Your most recent publication It's Warm was written and illustrated by you. What was the message you wished to convey in the book, and what do you think is the most important part of the book?

A. As an illustrator, you receive a story from someone else, and you start painting. But from some 20 years ago, I accepted almost no stories written by someone else because I wanted to write about my life down in the countryside.

Q. While you were working on your latest book, what did you feel was the difference between illustrating for someone else and writing and illustrating at the same time?

A. When you write your own story, there can be difficulties, but eventually, you're dipping into your own experiences. I also contemplated deeply on the message that my writing had. I wrote the story, but I also tried to look at it from a stranger's point of view. I kept asking myself questions about the story, going in and out of the story as the writer and a reader. In this process, I think I went to the far reaches of my consciousness then, like I was reaching for an unconscious state. In the case of It's Warm, the initial sketches for my illustrations were deeply affected by two broad elements, or memories that I have. One would be when I first saw a chicken trapped inside a wire cage at a market in Gapyeong and the other was when I saw a child whose birth name was 'potato'. When recalling memories, one may remember fleeting emotions from their experiences. I continuously tried to confirm whether the message I was telling was accurate, and in that process, you reach an emotional peak, and I tried to stay in that mindset for as long as I could. When you're illustrating someone else's work, this doesn't occur easily, but I think it was possible because it was my story. When looking back on my previous experiences, The Hen Who Dreamed She Could Fly had good results because I felt one with the story. It's somewhat a physical reaction, and I think it happens more often when I write my own stories.

I won't stop reinterpreting It's Warm, which I wrote and illustrated.

Q. Your affection for It's Warm is probably quite substantial because it was the first book where you also wrote the story in addition to illustrating it. Were there any differences from your previous work?

A. In 2010, I published a collection of some 50 nursery rhymes. This was the very first time I had to express something in words and not through visual art. My art had been shown in competitions and exhibitions, but one day I stumbled upon poetry, and I started writing poems. When I created my collection of poems, the biggest hardship I had was working with words. The pressure was also on because these weren't spoken words that disappear once you say them, but written words that remain on record.

Q. When you're selecting stories to illustrate, what are your most important criteria? We'd like to know if you have specific standards unique to yourself.

A. I try to look for sincerity from the story and how polished it is. The biggest element for me, I think, would be sincerity. If you can't agree with the author's view of the world or values, then you can't illustrate their stories. I started illustrating for story-writers 30 years ago, and I've published over 100 books since. Even when I illustrated books to put food in my mouth, I needed to find an understanding of the story content. When that understanding is lacking, it's hard to express stories in art form. Even when you agree with the content and have an understanding, the illustrations might not happen. Personally, I believe I have limitations when it comes to quiet stories. My illustrations go best with stories that are active.

In the past, I tried to hide this strength in my art

Q. Many associate your work with traditional Korean art, saying your illustrations have many overlapping elements. Could you list the pros and cons of that when it comes to exporting your work overseas?

A. I don't intentionally lean on Korean tradition when illustrating stories. I try to stick to drawing what I feel, and the things I've experienced and seen are reflected in my work. I am Korean, and the aspects of my life lived as a Korean person are probably why the Korean psyche can naturally be spotted in my work. It's not like I consciously remind myself how to illustrate in a certain style.

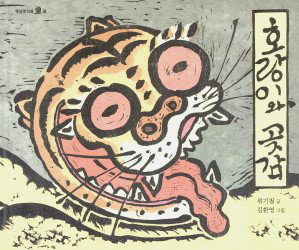

The Tiger and Persimmon

In the case of The Tiger and Persimmon (Kookmin Books), we received a lot of feedback from foreign readers. I think it was more so because the illustrations were made with carved wooden prints. It wasn't a deliberate decision to have the illustrations look like traditional Korean art - the illustrations came about after deep thinking on what they should look like. I actually think one should avoid the term 'Korean' when describing art because traditional art exists elsewhere too, and there are many elements that overlap between cultures. At times I ask myself whether the term 'Orientalism' that is used by the West to describe Asia is all-positive.

Q. Your work was selected to represent Korea at the Biennial of Illustration Bratislava and also included in an artist reference book created by the Korean Board on Books for Young People (KBBY). Like these examples, your work is continuously being introduced to readers outside South KoreA. How do you feel about the opportunities being given to you to reach foreign readers? We're also curious to learn if you have a sense of duty as an artist who is helping Korean children's books become known elsewhere.

A. The history of Korean picture books now spans roughly 30 years. In my case, I have worked as an artist and a poet. I've launched a magazine on nursery rhymes, and I've also worked with various formats like animations or comics. I feel a slight bit of pressure introducing myself to foreign readers as a picture book illustrator because I've dabbled in many other things. The Hen Who Dreamed She Could Fly was released in 30 different countries and for nearly all of the exported publications, the illustrations accompanied the story. It was surprising to me that all of these countries decided to accept the illustrations despite some cultural disparities. Often you will see stories exported, but illustrations rarely get the same treatment when it comes to children's books. It was a relief that there wasn't much pushback against the illustrations when the book was exported to other countries. The chickens, ducks or tree leaves were not detailed nor accurate, but I truly focused on the illustrations, and that is why readers are moved, I believe. When readers in other countries read the book, the book will deliver Korean elements to them, and it is my hope that they will have positive thoughts when they think of KoreA.

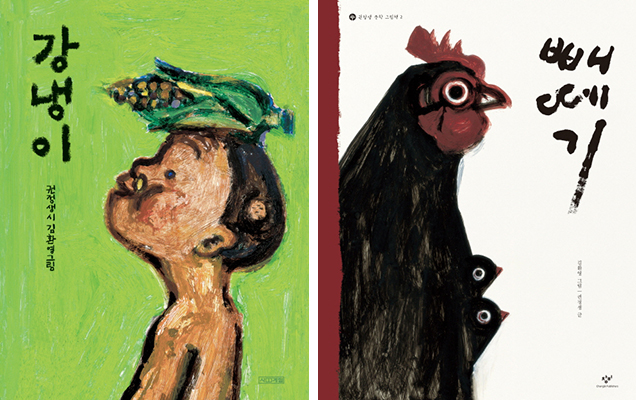

Corn, Bbaeddaegi

We are curious to know what the reader response

Q. What do you think are the unique or appealing aspects of your art for readers outside South Korea?

A. That would be the distinctiveness South Korea has in general. Corn and Bbaeddaegi all take place during the Korean War. They're very real stories written for children. I think one of the things all mankind shares is pain. Contemporary Korean history includes the military rule of the Korean peninsula by Japan and the Korean War. The Korean War was a case in which a people were divided into two, aiming guns at each other. The Korean peninsula is still divided today, and that split is the result of that war.

Q. What kind of projects would you like to undertake going forward? Do you have a message you would like to tell children or readers in general with your work? Please tell us about your future plans.

A. I will continue writing and drawing. I would like to open up my life and show the stories I have inside me. It took me a long time to complete something that is wholly mine, but I now want to keep expressing the space I live in and what goes on in my heart. My key themes will be life and peace, but I'm not sure what the format will be. I'm also curious to know what my future path will be like. Even if I tell stories on life and peace, it will eventually be a process in which I search for myself, as I go deep into my future projects. I am planning my second book after It's Warm and this too, carries a world that is whole and warm.

Arranged by KIM Young-Ihm

|

Pre Megazine

-

Jakkajungsin Publishing Co.

VOL.69

2024.04 -

Writer Yun Jung-Eun

VOL.69

2024.04 -

Jumping Books Publishing House

VOL.68

2024.03 -

Writer Kim Hwa-Jin

VOL.68

2024.03 -

Publisher Hyohyung

VOL.67

2024.02 -

Writer Minha

VOL.67

2024.02 -

Almond Publishing

VOL.66

2024.01 -

Writer Kwon Jung-Min

VOL.66

2024.01 -

Hakgojae Publishers

VOL.65

2023.12 -

Writer Kim Hye-Jung

VOL.65

2023.12 -

Eidos Publishing House

VOL.64

2023.11 -

Writer Hwang In-Chan

VOL.64

2023.11 -

Munhakdongne

VOL.63

2023.10 -

Writer Chang Kang-myoung

VOL.63

2023.10 -

Happywell Publishing

VOL.62

2023.09 -

Writer Baik Soulinne

VOL.62

2023.09 -

Dasan Contents Group (Dasan Books)

VOL.61

2023.08 -

Writer Lim Kyoung-Sun

VOL.61

2023.08 -

SpringSunshine Publishing Co.

VOL.60

2023.07 -

Writer Lee Kyung-Hye

VOL.60

2023.07 -

Human Cube

VOL.59

2023.06 -

Doctor Jeong Jae-Seung

VOL.59

2023.06 -

Anonbooks

VOL.58

2023.05 -

Writer Son Bo-Mi

VOL.58

2023.05 -

Namhaebomnal

VOL.57

2023.04 -

Writer Kim Bo-Young

VOL.57

2023.04 -

Hugo Publishing

VOL.56

2023.03 -

Writer Cho Kwang-Hee

VOL.56

2023.03 -

Balgeunmirae Publishing Co.

VOL.55

2023.02 -

Writer Lee Byung-Ryul

VOL.55

2023.02 -

Wisdom House, Inc

VOL.54

2023.01 -

Writer Jeong Jia

VOL.54

2023.01 -

Humanitas

VOL.53

2022.12 -

Writer Kim Yeon-Su

VOL.53

2022.12 -

Songsongbooks

VOL.52

2022.11 -

Writer Eun Hee-Kyung

VOL.52

2022.11 -

Bombom Publishing Co.

VOL.51

2022.10 -

Writer Jiwon Yu

VOL.51

2022.10 -

Hangilsa Publishing Co., Ltd.

VOL.50

2022.09 -

Writer Kim Won-Young

VOL.50

2022.09 -

Moksu Publishing Company

VOL.49

2022.08 -

Writer Yoo Sun-Kyong

VOL.49

2022.08 -

Next Wave

VOL.48

2022.07 -

Writer Park Sang-Young

VOL.48

2022.07 -

A Thousand Hopes

VOL.47

2022.06 -

Writer Bora Chung

VOL.47

2022.06 -

Woongjin ThinkBig

VOL.46

2022.05 -

Dr. Oh Eun-Young

VOL.46

2022.05 -

JECHEOLSO Publishing House

VOL.45

2022.04 -

Writer Jang Ryu-Jin

VOL.45

2022.04 -

Changbi Publishers

VOL.44

2022.03 -

Writer Kim Ho-Yeon

VOL.44

2022.03 -

Mati Books

VOL.43

2022.02 -

Writer Lee Kkoch-Nim

VOL.43

2022.02 -

Picturebook Gongjackso

VOL.42

2022.01 -

Writer Kim Sang-Wook

VOL.42

2022.01 -

Writer So-yeon Park

VOL.42

2022.01 -

Writer Yoo Eun sil

VOL.42

2022.01 -

Kungree Press

VOL.41

2021.12 -

Writer Kim Lily

VOL.41

2021.12 -

Writer Park Yeon-jun

VOL.41

2021.12 -

Writer Yi Hyeon

VOL.41

2021.12 -

A deeper world told through picture books 'Iyagikot Publishing (Story Flower)'

VOL.12

2019.06 -

Author Jeon Min-hee

VOL.12

2019.06 -

Illustrator Kim Hwan-Young

VOL.13

2019.07 -

Travelers sailing through the sea of knowledge - 'Across Publishing Group Inc.'

VOL.13

2019.07 -

Genre Novel Publisher 'Arzak Livres'

VOL.14

2019.08 -

Author Lee Yong-han

VOL.14

2019.08 -

Wookwan Sunim

VOL.15

2019.09 -

East-Asia Publishing

VOL.15

2019.09 -

Author Jo Jung-rae

VOL.16

2019.10 -

EunHaeng NaMu Publishing

VOL.16

2019.10 -

Writer Heo Kyo bum

VOL.40

2021.11 -

Writer Kim So-Young

VOL.40

2021.11 -

Author-illustrator Kim Sang Keun

VOL.40

2021.11 -

ACHIMDAL BOOKS

VOL.40

2021.11 -

Author Kang Gyeong-su

VOL.17

2019.11 -

Moonji Publishing Belongs to the Literary Community

VOL.17

2019.11 -

Author Kim Yun-jeong

VOL.18

2019.12 -

I-Seum

VOL.18

2019.12 -

Kim Cho-Yeop

VOL.19

2020.02 -

Creating a window into the future with books

VOL.19

2020.02 -

Author Serang Chung

VOL.20

2020.03 -

Hey Uhm

VOL.20

2020.03 -

Writer Lim Hong-Tek

VOL.21

2020.04 -

BIR

VOL.21

2020.04 -

Writer Song Mikyoung

VOL.39

2021.10 -

Author-illustrator Kim Dong Su

VOL.39

2021.10 -

Writer Lee Seula

VOL.39

2021.10 -

Tabi Books

VOL.39

2021.10 -

Writer Kim Soo-hyun

VOL.38

2021.09 -

Author-illustrator Lee Myoung Ae

VOL.38

2021.09 -

Writer Hwang Sunmi

VOL.38

2021.09 -

Kidari Publishing Co.

VOL.38

2021.09 -

Writer Sohn Won-Pyung

VOL.22

2020.05 -

Woods of Mind's Books

VOL.22

2020.05 -

Writer Heungeul

VOL.23

2020.06 -

Gloyeon

VOL.23

2020.06 -

Maumsanchaek

VOL.24

2020.07 -

Winners of the 2021 Bologna Ragazzi Award

VOL.37

2021.08 -

Picture book artist Lee Suzy

VOL.37

2021.08 -

Author-illustrator Yi Gee Eun

VOL.37

2021.08 -

Hubble

VOL.37

2021.08 -

Writer Baek Se-Hee

VOL.25

2020.08 -

Bearbooks Inc.

VOL.25

2020.08 -

Author Baek Hee-Na

VOL.26

2020.09 -

Yuksabipyoungsa

VOL.26

2020.09 -

Writer Kang Hwa-Gil

VOL.27

2020.10 -

Kinderland (Bandal)

VOL.27

2020.10 -

Writer Ha wann

VOL.36

2021.07 -

Author-illustrator Myung Soojung

VOL.36

2021.07 -

Writer Jung Yeo-Wool

VOL.36

2021.07 -

Publisher EcoLivres

VOL.36

2021.07 -

Writer Lee Geumi

VOL.28

2020.11 -

Sakyejul

VOL.28

2020.11 -

Writer Kim Keum-Hee

VOL.29

2020.12 -

Geulhangari

VOL.29

2020.12 -

Writer Cheon Seon-Ran

VOL.30

2021.01 -

Hyang Publishing House

VOL.30

2021.01 -

Writer Lee Hee-Young

VOL.31

2021.02 -

Sanzini

VOL.31

2021.02 -

Publisher Prunsoop

VOL.32

2021.03 -

Writer Sim Yun-Kyung

VOL.32

2021.03 -

Hanbit Media

VOL.35

2021.06 -

Hyeonamsa

VOL.33

2021.04 -

Author-illustrator Noh Inkyung

VOL.33

2021.04 -

Writer Cho Won-Jae

VOL.35

2021.06 -

Writer Kim Jung-Mi

VOL.34

2021.05 -

Safehouse Inc.

VOL.34

2021.05