|

Discussions on introducing typographical copyright

2019.11.04

1. Summary of typographical copyright

Typographical copyright refers to the proprietary publishing rights for typographical arrangements of published editions. Typographical copyright is being acknowledged as a type of neighboring right to protect the efforts and investments of publishers that play a key role in delivering published material through planning, providing authorship support, editing (setting layouts, proofreading and revising), designing and producing. Typographical copyright was first implemented to U.K. copyright law in 1956. Currently as of 2017, 26 countries around the world including Spain, Mexico, Australia, New Zealand and Ireland address typographical copyright in their copyright law. Elements like page style, the composition of the published work, layout and other physical features all fall under typographical copyright, and the publisher is the holder of that right. The lifetime of typographical copyright can last 25 years in 20 countries like the United Kingdom and up to 50 years in five countries including Mexico. In China, the right lasts up to a decade. In 20 countries like the United Kingdom, typographical copyright can only be used for specific publications like written works, while the remaining six countries do not have such limitations.

2. Discussions on the introduction and legalization of typographical copyright in South Korea

The bill was introduced to equally protect the rights of publishers who have invested in surface designs through typographical copyright.

The term 'typographical copyright' is thought to have been first used in South Korea in the December issue of Publishing Culture from the Korean Publishers Association in 1985. The term was used in a piece called 'Typographical Copyright as a Right for Publishers', translated from a Japanese publishing magazine. Afterwards, through the 1990s and 2000s, there were constant demands for the introduction of typographical copyright in regards to amendments to South Korea's copyright law. However, the demands could not be backed up with structured surveys and research at that time. In 2010 amid diverse discussions to increase electronic publishing, efforts were made to review typographical copyright. And in 2011, the Korean Publishers Association released an unprecedented report on the subject called “Research for the Introduction of Typographical Copyright” which offered comprehensive research results. The association also hosted a seminar on the paper. This, in turn, opened a new opportunity for typographical copyright to be used in South Korea, but no further accomplishments were made. In 2011, South Korea's publishing industry was faced with a more urgent task of establishing an official body for the promotion of published works (currently KPIPA), and after that it needed to resolve the issue of properly setting fixed rates for books. There was simply a lack of time to set aside interest for typographical copyright.

3. Two alternatives

The publishing industry considers the introduction of typographical copyright as an urgent task.

The reason why those in the publishing industry demand the introduction of typographical copyright is due to the perception that publishers' rights are not being fully protected due to current copyright laws or prevalent practices when it comes to publishing contracts. To protect the rights of publishers, expanding current efforts to implement typographical copyright is certainly one way, but the introduction of other policies may succeed in bringing about similar results or better. There are two alternatives.

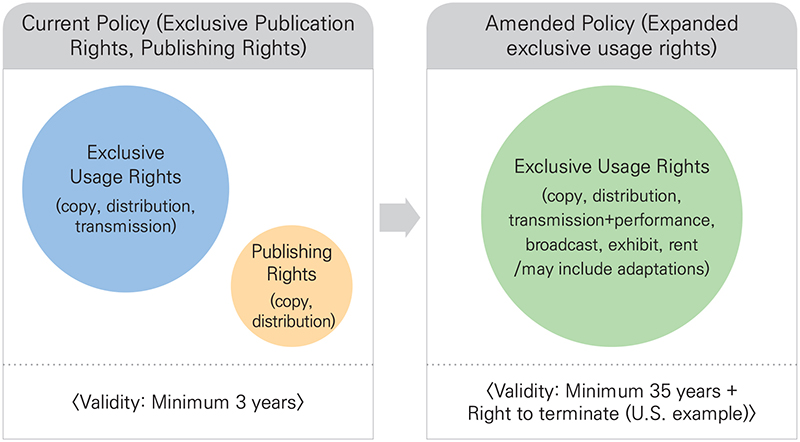

(1) Exclusive publishing rights expanded to absorb publishing rights (alternative 1) The first alternative would be to expand the meaning of the current exclusive publishing right to something similar to what the United States has in terms of exclusive usage permission rights and combine publishing rights with this new policy. It has been seven years since the implementation of exclusive publishing rights, but the public is now accustomed to seeing digital publications and the policy even results in confusion at times regarding compensation collection and other issues. The combination of the two would be possible as there is no solid reason to manage online and offline publications separately at this point. Another fact to be considered is that if the scale of exclusive publishing rights are expanded and the lifetime of those rights are extended to 35 years to match policy in the United States, there would be no need to implement typographical copyright separately.

〈Picture 1〉 Comparison between current publishing rights, exclusive publishing rights

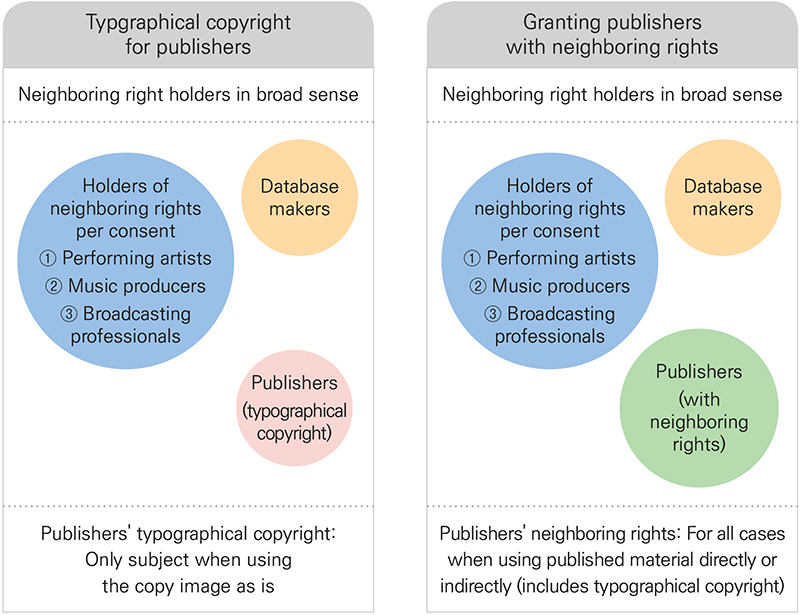

(2) Grant neighboring rights to publishers (alternative 2) Another alternative would be to grant neighboring rights to publishers. Once granted, publishers would enjoy the same rights as do performing artists, music producers and broadcasting professionals or database makers. This would enable publishers to copy, distribute and transmit published material. Mexico has the longest copyright protection period in the world, which is 100 years after the author's date of death. Mexico also acknowledges typographical copyright, as well as its neighboring copyright, and the lifetimes for these are 50 years post-publication. This alternative would grant a wider range of rights compared to the U.K. version of typographical copyright and would powerfully protect publishers. It would also complement any gaps or limitations typographical copyright policies may have, as some have pointed out there are limited upsides in right protection in typographical copyright for electronic publications.

〈Picture 2〉 Comparison between publishers' typographical copyright and implementation of neighboring rights

Although the publishing industry has addressed typographical copyright introduction as an urgent task, industry professionals are likely open to other alternatives. The main issue is there is an urgency at hand to implement a similar policy, whether it be typographical copyright, a policy for expanded exclusive usage rights or granting publishers neighboring rights.

Written by Park Ik-soon (Korean Publishing and Copyright Research Institute) Park Ik-soon (Korean Publishing and Copyright Research Institute) |

Pre Megazine

-

The Influence and Application of AI Translators on the Publishing Industry and the Import and Export of Copyrights

VOL.69

2024.04 -

Korea is Now All About Plants!

VOL.69

2024.04 -

Korean Literature in the American Market

VOL.69

2024.04 -

The World Grows in the Wait

VOL.69

2024.04 -

Why We Read Fiction

VOL.69

2024.04 -

Recent Status of Korean Webnovels

VOL.69

2024.04 -

How Book Club Platforms Captivate Readers

VOL.68

2024.03 -

For Planet Earth, Where We Coexist

VOL.68

2024.03 -

More and More Chinese Readers Are Starting to Pay Attention to Korean Literature

VOL.68

2024.03 -

Warm Hope in a Cold City

VOL.68

2024.03 -

The Wisdom to Survive in the Ever-changing World

VOL.68

2024.03 -

Publishers and YouTube: Current Status and the Future

VOL.68

2024.03 -

K-Illustrations in One Spot!

VOL.68

2024.03 -

Publishing Strategies Targeting the MZ Generation

VOL.67

2024.02 -

AI is Changing Our Everyday Life

VOL.67

2024.02 -

The Most Korean is the Most Global

VOL.67

2024.02 -

The Jolly Shelter and Home of the Mangwon-dong Brothers!

VOL.67

2024.02 -

Reading: Sorting Out the Unchanging from the Changing

VOL.67

2024.02 -

A Call for an Evolutionary Level of Imagination: Replacement of Dominant Species

VOL.67

2024.02 -

Starting Life With Books, Bookstart Korea

VOL.67

2024.02 -

2023 Publishing Statistics & 2024 Publishing Market Outlook

VOL.66

2024.01 -

2020-2022 Bestsellers: Korean Humanities Books

VOL.66

2024.01 -

Korean Picture Books Today

VOL.66

2024.01 -

Everything About Coffee We Love

VOL.66

2024.01 -

Enjoy the Taste and Scent of Korea With Genre Literature

VOL.66

2024.01 -

The Street of Youth: Shinchon, Seoul

VOL.66

2024.01 -

Time to Dive Into Korean History

VOL.66

2024.01 -

Marketing in Korean Bookstores: Recovered Editions & Book-funding

VOL.65

2023.12 -

2020-2022 Bestsellers: Korean Self-help Books

VOL.65

2023.12 -

Artificial Intelligence (AI) Use Cases in the Korean Publishing Market

VOL.65

2023.12 -

Modern Korean Art

VOL.65

2023.12 -

Successful Publication Cases of Korean Children’s Books in China

VOL.65

2023.12 -

Human Acts, One Step Closer to a Painful Memory

VOL.65

2023.12 -

Endless Possibilities in Korean Science Books and SF

VOL.65

2023.12 -

Korean Libraries’ Various Book-reading Activities and Cooperation Efforts with the Publishing Industry

VOL.64

2023.11 -

2020-2022 Bestsellers: Korean Picture Books

VOL.64

2023.11 -

Legal and Ethical Issues and Implications of AI-based Creations

VOL.64

2023.11 -

The Dwelling Culture of Korea

VOL.64

2023.11 -

Bringing Korean Literature to Hebrew Readers

VOL.64

2023.11 -

Re-creating Pyeongsa-ri from the Book Land

VOL.64

2023.11 -

Living a Life in Korea in 2023

VOL.64

2023.11 -

Bookshelves are Going into TVs!

VOL.63

2023.10 -

2020-2022 Bestsellers: Korean Fiction

VOL.63

2023.10 -

The AI Storm Sweeps the Publishing Industry: Chat GPT

VOL.63

2023.10 -

K-Food Captivates the World

VOL.63

2023.10 -

A Special Convenience Store that Mesmerized Japanese Readers!

VOL.63

2023.10 -

A Place Where You Can Make Unforgettable Memories: Hakuda Photo Studio

VOL.63

2023.10 -

The Women We Don’t Want to Know

VOL.63

2023.10 -

Today and Tomorrow of the Korean Standard Publishing Distribution Data Hub System

VOL.62

2023.09 -

Winning and Nominated Works for International Literary Awards in 2022

VOL.62

2023.09 -

From YouTube to Books

VOL.62

2023.09 -

The Era of Dance is Coming

VOL.62

2023.09 -

Current Status and Prospects of Korean Literature in Arab Countries

VOL.62

2023.09 -

Fly on a Witch’s Vacuum Cleaner: Witches’ Delivery

VOL.62

2023.09 -

Fiction is a Journey Into the Complexity of Human Identity

VOL.62

2023.09 -

Today and Future of Korean Digital Publishing

VOL.61

2023.08 -

Korean Literary Magazines and Literary Webzines

VOL.61

2023.08 -

From the Margins to the Center: Korean Mystery Literature

VOL.61

2023.08 -

K-pop and the World!

VOL.61

2023.08 -

Mexican Readers and Korean Literature

VOL.61

2023.08 -

Where the Children from the Book Children of Kwaeng-I-Bu-Ri Village Used to Play

VOL.61

2023.08 -

Radio DJ’s Pick

VOL.61

2023.08 -

The 2023 Seoul International Book Fair and the K-Book Copyright Market

VOL.60

2023.07 -

Book Pricing Strategies in Korea

VOL.60

2023.07 -

Translation and Publication Support Projects in Korea

VOL.60

2023.07 -

My Brilliant Life

VOL.60

2023.07 -

Bringing Hwang Sun-Mi books to Türkçe Readers

VOL.60

2023.07 -

Hahn Moo-Sook House

VOL.60

2023.07 -

Professor of Korean Language and Literature & Literary Critic’s Pick

VOL.60

2023.07 -

The Trend and Prospects of the Self-help Book Market in Korea

VOL.59

2023.06 -

E-Book Platforms in Korea

VOL.59

2023.06 -

Travelers Return After COVID-19

VOL.59

2023.06 -

Divorce Attorney Shin

VOL.59

2023.06 -

The Marketing Strategy for the Chinese Version of The Mummy Book

VOL.59

2023.06 -

The Library of Mystery Literature

VOL.59

2023.06 -

Japanese Translator’s Pick

VOL.59

2023.06 -

Reader-friendly Publication Marketing

VOL.58

2023.05 -

2023 K-Book Copyright Market & Seoul International Book Fair

VOL.58

2023.05 -

The Current and Future Ecosystem of Published Comics

VOL.58

2023.05 -

D.P.

VOL.58

2023.05 -

Flowers of the Orient – Bringing Korean Gems to Polish Readers

VOL.58

2023.05 -

Chaeg Bar

VOL.58

2023.05 -

Korean Theatre Director’s Pick

VOL.58

2023.05 -

Domestic Video Content Originating from Literature

VOL.57

2023.04 -

Paju Bookcity

VOL.57

2023.04 -

“Restructuring of Family” Becoming Inevitable

VOL.57

2023.04 -

Reborn Rich

VOL.57

2023.04 -

The Uncanny Convenience Store’s Magical Journey in Taiwan

VOL.57

2023.04 -

Sehan Bookstore

VOL.57

2023.04 -

Singer-Songwriter’s Pick

VOL.57

2023.04 -

How are Regional Publishers in Korea Thriving?

VOL.56

2023.03 -

KPIPA hosts the 2023 Visiting Korean Book Fair

VOL.56

2023.03 -

Export Status of Korean Webnovels and Webtoons

VOL.56

2023.03 -

Namhansanseong Fortress

VOL.56

2023.03 -

Korean Books Published by Haru Publisher Indonesia

VOL.56

2023.03 -

Book Plant

VOL.56

2023.03 -

Illustrator’s Pick

VOL.56

2023.03 -

“PDF/POD” - Korean Publishing Market Develop into Diverse Formats

VOL.55

2023.02 -

Arts Council Korea’s Munhak Nanum Book Distribution Project

VOL.55

2023.02 -

The Future of Korean Novels: Gen-MZ Writers

VOL.55

2023.02 -

Diary of a Murderer

VOL.55

2023.02 -

Successful Import Case of Korean Literature in the U.S.A.

VOL.55

2023.02 -

Chosochaekbang

VOL.55

2023.02 -

Museum Curator’s Pick

VOL.55

2023.02 -

New Approaches to Education in the Korean Publishing Industry

VOL.54

2023.01 -

Where Writers and Readers Meet

VOL.54

2023.01 -

The “Most Korean” Features Penetrate the World

VOL.54

2023.01 -

International Human Rights Expert, Professor Chung Chin-Sung

VOL.54

2023.01 -

Korean Books Published in Thailand through Nanmeebooks

VOL.54

2023.01 -

Namsan Public Library

VOL.54

2023.01 -

Elementary School Teacher’s Pick

VOL.54

2023.01 -

“Trend Forecasters” Dominate Bookstores in Korea

VOL.53

2022.12 -

Art Critic Professor Yu Hong-June

VOL.53

2022.12 -

Korean and Japanese Publishers Join Hands

VOL.53

2022.12 -

Seoul Metropolitan Library

VOL.53

2022.12 -

Korean Editor’s Pick

VOL.53

2022.12 -

Current Employment Status in the Korean Publication Industry

VOL.53

2022.12 -

The Gates to K-Books

VOL.53

2022.12 -

Korean Bookstores Dominated by Screenplays and scripts

VOL.52

2022.11 -

Cultural Anthropologist, Professor Chohan Haejoang

VOL.52

2022.11 -

K-Book Trend in Latin America Seen Through the Chilean Publishing Market

VOL.52

2022.11 -

Jeongdok Public Library

VOL.52

2022.11 -

Former Newscaster and YouTube Creator’s Pick

VOL.52

2022.11 -

MCST Announces the 2022-2026 Publishing Industry Promotion Plan

VOL.52

2022.11 -

Publishers’ Book Clubs

VOL.52

2022.11 -

The “Healing Fiction” Fever

VOL.51

2022.10 -

Professor Kim Ho-Dong, the World-Renowned Scholar in Central Eurasian History

VOL.51

2022.10 -

Foreign Agency on Publishing K-Books in Other Countries in Cooperation with Korean Agency

VOL.51

2022.10 -

NaeRule Gunaseo Supuro Library (Stream & Forest Library)

VOL.51

2022.10 -

A Diplomat’s Pick

VOL.51

2022.10 -

Achievements of the “One City, One Book” Movement

VOL.51

2022.10 -

Breathing Life Into Letters: Unique Hangeul Fonts

VOL.51

2022.10 -

The Adoption of the Public Lending Right, Requiring the Agreement of All Parties in the Publishing Industry

VOL.50

2022.09 -

Seen through Statistics: The Status of Offline Bookstores in Korea

VOL.50

2022.09 -

Fandom and Publishing

VOL.50

2022.09 -

Oh Kang-Nam, Professor of Comparative Religion

VOL.50

2022.09 -

Successful Import Case of Korean Literature in the U.K.

VOL.50

2022.09 -

Banyawol Station Building Small Library and Dongchon Station Building Small Library

VOL.50

2022.09 -

Copyright Agent’s Pick

VOL.50

2022.09 -

Trends in the Publishing Market in the First Half of 2022

VOL.49

2022.08 -

Audiobook Platforms in Korea

VOL.49

2022.08 -

Looking Back on the 65th Seoul International Book Fair in 2022

VOL.49

2022.08 -

Dr. Kim Myung-Ja

VOL.49

2022.08 -

Book Trend in Korea Eyed by the Russian Publishing Market in the 2020s

VOL.49

2022.08 -

“Lotus in the Library” in Jeonju

VOL.49

2022.08 -

Travel Bookstore’s Pick

VOL.49

2022.08 -

Various Book Festivals in Korea

VOL.48

2022.07 -

Promoting La Torre and Korean Literature in Italy

VOL.48

2022.07 -

Publishing Industry Full of Consolation and Sympathy in the Post-COVID-19 Era

VOL.48

2022.07 -

Public Health Specialist and Socialist, Professor Kim Seung-Sup

VOL.48

2022.07 -

Uijeongbu Music Library

VOL.48

2022.07 -

Foreigner Living in Korea’s Pick

VOL.48

2022.07 -

Korea’s Writing Platforms

VOL.48

2022.07 -

On the 100th Anniversary of Children’s Day, How Did the Korean Publishing Industry Spend the Day?

VOL.47

2022.06 -

103-Year-Old Philosopher Kim Hyung-Seok

VOL.47

2022.06 -

12 Years of Publishing Korean Books in Vietnam

VOL.47

2022.06 -

The Factory of Contemporary Arts in Palbok, Poplar Tree Picture Book Library

VOL.47

2022.06 -

A Korean Literary Translator’s Pick

VOL.47

2022.06 -

The Vulnerability of Production Focused on Paper Books

VOL.47

2022.06 -

Seoul Book Institute (SBI)

VOL.47

2022.06 -

Korea’s Publishing Trend - The World Literature Complete Collection

VOL.46

2022.05 -

Types of Korean Magazines based on Keywords

VOL.46

2022.05 -

Newsletter of Korean Publishers

VOL.46

2022.05 -

Brain Engineer Jeong Jae-Seung Seeks Innovative Disciplinary Convergence

VOL.46

2022.05 -

Dollagoot Dream Department Store in the Taiwanese Publishing Market

VOL.46

2022.05 -

Goyang Aram Nuri Library

VOL.46

2022.05 -

Secondhand Bookstore Manager’s Pick

VOL.46

2022.05 -

Korean Book Publishers Eye Webnovels and Webtoons

VOL.45

2022.04 -

Korean Book Designer’s Pick

VOL.45

2022.04 -

A Retirement-encouraging Society in the Era of a 100-year Life Expectancy

VOL.45

2022.04 -

2022 Hans Christian Andersen Award Winner Suzy Lee's Books

VOL.45

2022.04 -

Professor Lim Jie-Hyun’s Realistic and Reflective View on Korean History

VOL.45

2022.04 -

K-BOOK Import Case in Germany

VOL.45

2022.04 -

Gangseo Miracle Library, Busan

VOL.45

2022.04 -

PLATFORM P

VOL.45

2022.04 -

The Comeback of Best-selling Books is Thanks to Youtube

VOL.44

2022.03 -

The Era of the Metaverse: Will It Allow Authors and the Publishing Industry to Coexist?

VOL.44

2022.03 -

2022 Overseas Publication Grants

VOL.44

2022.03 -

The Warmth of Science and Life by Professor Choi Jae-Cheon

VOL.44

2022.03 -

Successful Import Case of Korean Literature in Japan

VOL.44

2022.03 -

Anyang Pavilion (Books on Contemporary Public Art)

VOL.44

2022.03 -

Music Braille Transcriber’s Pick

VOL.44

2022.03 -

“Illness Narratives” A Detailed Reflection of our Society

VOL.43

2022.02 -

Deep Insights into the World from the Great Scholar Lee O-Young’s Viewpoint

VOL.43

2022.02 -

China Export Case

VOL.43

2022.02 -

Art Library Of Uijeongbu

VOL.43

2022.02 -

Korean Food Critic’s Pick

VOL.43

2022.02 -

Collaboration of Reading Class at School and the Publishing Industry

VOL.43

2022.02 -

K-Literature: The Winners of Major International Literary Awards in 2021

VOL.43

2022.02 -

The Korean Book Importing Success Story of AST, a Russian Publisher

VOL.42

2022.01 -

K-Book Promotion and Exchange Event

VOL.42

2022.01 -

Korean Publishing Industry's Crisis and Its Future

VOL.42

2022.01 -

Korean Publishing Industry Current Trends in 2021 and Projections in 2022

VOL.42

2022.01 -

The Life of Dr. Park Moon-Ho and the Journey to Finding the Origin of Thought

VOL.42

2022.01 -

Pohang, Gyeongsangbuk-do

VOL.42

2022.01 -

Movie Critic’s Pick

VOL.42

2022.01 -

Reviews, Review Journals, and the New Review Culture

VOL.41

2021.12 -

Korean Books Seen From a Foreign Blog’s View

VOL.41

2021.12 -

Current Status of Publications for Seniors in Korea

VOL.41

2021.12 -

A Genre for All Generations: Young Adult

VOL.41

2021.12 -

Marketing Strategies for Lane 5 in the Taiwanese Publishing Market

VOL.41

2021.12 -

Wonju, Gangwon-do

VOL.41

2021.12 -

Korean Novelist’s Pick

VOL.41

2021.12 -

A Diagnosis of South Korea's E-book Market Amid Subscription Competition

VOL.12

2019.06 -

The History and Characteristics of South Korean Copyright Legislation

VOL.12

2019.06 -

Nami Island International Children's Book Festival 2019

VOL.12

2019.06 -

The Growth of Korean Audio Books, Celebrities Attract Listeners

VOL.12

2019.06 -

KL Management's Export Success Case for Novel Almond

VOL.12

2019.06 -

The City of Islands and Stories,Tongyeong of South Gyeongsang Province

VOL.12

2019.06 -

Sales of key South Korean bookstores

VOL.13

2019.07 -

South Korea’s Key Publishing Related Organizations

VOL.13

2019.07 -

By Embracing History and Culture, Incheon Blossoms with Literature

VOL.13

2019.07 -

How Eduwill successfully exported the PERFECT TOPIK series to China and Taiwan

VOL.13

2019.07 -

Essays that touch the heart

VOL.13

2019.07 -

2019 Seoul International Book Fair - Arrival

VOL.13

2019.07 -

South Korea's Global Book Exports

VOL.14

2019.08 -

South Korea's Standard Publishing Contracts and Adaptation Rights

VOL.14

2019.08 -

South Korea's Fixed Book Price Policy

VOL.14

2019.08 -

South Korea's Publishing Industry in H1 2019 and Forecasts for H2

VOL.14

2019.08 -

North Korea Seen Through Books, and the Unification of the Korean Peninsula

VOL.14

2019.08 -

South Korea's National Institute of Ecology - Known for publishing content acclaimed worldwide

VOL.14

2019.08 -

Hongdae, a neighborhood with a free and unique culture

VOL.14

2019.08 -

Discussions on public lending rights and tasks ahead

VOL.15

2019.09 -

Social media, or word-of-mouth marketing a must-have for one-person publishing companies

VOL.15

2019.09 -

Busan

VOL.15

2019.09 -

e-future, a business specializing in ELT content

VOL.15

2019.09 -

K-Book in Berlin

VOL.15

2019.09 -

South Korean web novels become a trend of their own

VOL.15

2019.09 -

Visual adaptation rights for books and sales

VOL.16

2019.10 -

South Korea's Imprint System in Publishing

VOL.16

2019.10 -

Paju Book City

VOL.16

2019.10 -

Round Ground

VOL.16

2019.10 -

Books recommended by bookstore MDs and librarians

VOL.16

2019.10 -

Great places to meet South Korean books

VOL.16

2019.10 -

Literary Awards of Korea

VOL.40

2021.11 -

The Current State of Korea’s Libraries and Their Relation to the Publishing Industry

VOL.40

2021.11 -

TV Producer’s Pick

VOL.40

2021.11 -

Cheongju, Chungcheongbuk-do

VOL.40

2021.11 -

Success Stories of Japanese Publisher Kobunsha – Importer of Korean Books

VOL.40

2021.11 -

Advanced Korea: Finding the Right Path for Society

VOL.40

2021.11 -

Book Communities Create a New Cradle for Readers

VOL.40

2021.11 -

Discussions on introducing typographical copyright in South Korea

VOL.17

2019.11 -

South Korea's policies to promote reading and reading movements

VOL.17

2019.11 -

A New Joy Found in Daejeon - Tiny Bookstores

VOL.17

2019.11 -

Published in more than 40 countries, an unprecedented achievement in Korean literature

VOL.17

2019.11 -

Books and Writers of the Year Selected by Bookstores

VOL.17

2019.11 -

South Korean Books at International Book Fairs in 2019

VOL.17

2019.11 -

South Korea's publishing market and distribution structure

VOL.18

2019.12 -

South Korea's publishing market based on category

VOL.18

2019.12 -

Seoul's Tongin-dong

VOL.18

2019.12 -

Hwang Sun-mi, Author of The Hen Who Dreamed She Could Fly

VOL.18

2019.12 -

South Korea's literary awards and competitions of 2019

VOL.18

2019.12 -

South Korea's online platforms where readers can meet genre literature

VOL.18

2019.12 -

2020 Overseas Publication Grants

VOL.19

2020.02 -

Current status of each field in the Korean publishing market ① Literature publication

VOL.19

2020.02 -

Suwon Independent Bookstores

VOL.19

2020.02 -

2019 Korean Novels that fascinated foreign readers

VOL.19

2020.02 -

Writer of the Year Award

VOL.19

2020.02 -

2020 Publication Trends in Korea

VOL.19

2020.02 -

International Exchange Grants

VOL.20

2020.03 -

Current status of each field in the Korean publishing market ② History Publication

VOL.20

2020.03 -

Fly High: Independent Bookstores near the Gimpo International Airport

VOL.20

2020.03 -

Korean Non-Fiction in the Southeast Asian Publishing Market

VOL.20

2020.03 -

Spring Literary Contests held by Newspapers

VOL.20

2020.03 -

Speech and Literature were the weapons of women

VOL.20

2020.03 -

Korea Foundation (KF) Publication Support Program

VOL.21

2020.04 -

Current status of each field in the Korean publishing market ③ Philosophical and Religious Publications

VOL.21

2020.04 -

The future of bookstores seen in GyeongJu

VOL.21

2020.04 -

Korean Children, Young People’s Literature

VOL.21

2020.04 -

Korea’s Flagship Literary Awards for Poems

VOL.21

2020.04 -

Books and Book Clubs

VOL.21

2020.04 -

Korea’s Literary Magazines

VOL.39

2021.10 -

The Current State of Subscription-Based Services of Korea’s Published Content

VOL.39

2021.10 -

Book-tuber’s Picks

VOL.39

2021.10 -

Gumi, Gyeongsangbuk-do

VOL.39

2021.10 -

Many Different Genres of Korean Novels Are Now Selling Abroad

VOL.39

2021.10 -

Food for Thought on Careers, Truthfully Portrayed in Essays

VOL.39

2021.10 -

Observing the Stature of K-Literature Through Foreign Literary Awards

VOL.39

2021.10 -

Facilitation of Sub-rights and Their Markets

VOL.38

2021.09 -

Essay Writer’s Picks

VOL.38

2021.09 -

Gangneung, Gangwon-do

VOL.38

2021.09 -

Korean Literary Works that Have Recently Made Their Debut in France

VOL.38

2021.09 -

K-Fantasy

VOL.38

2021.09 -

The MZ Generation Reads New Non-Fiction

VOL.38

2021.09 -

KAMS Publishing Korean Art : Overseas Publication Support Program

VOL.22

2020.05 -

Current status of each field in the Korean publishing market ④ Social Science Publications

VOL.22

2020.05 -

Songpa, Seoul

VOL.22

2020.05 -

Korean literature spreading across the world

VOL.22

2020.05 -

Korea’s Diverse Children’s Literature Awards

VOL.22

2020.05 -

The Creative World of Baek Heena

VOL.22

2020.05 -

E-book Platforms and the Meaning of “Original Content”

VOL.22

2020.05 -

Overseas Publication Grants 2020

VOL.23

2020.06 -

Current status of each field in the Korean publishing market ⑤ Science & Technology Publications

VOL.23

2020.06 -

Chuncheon

VOL.23

2020.06 -

Export Trend of Self-Development Books in Korea

VOL.23

2020.06 -

Literary Awards and Contests in the field of Genre Literature

VOL.23

2020.06 -

Why K-Books are drawing attention from across the world

VOL.23

2020.06 -

Integrated K-Book Platform

VOL.24

2020.07 -

Current status of each field in the Korean publishing market ⑥ Self-Development Publications

VOL.24

2020.07 -

Jeonju, Jeollabukdo

VOL.24

2020.07 -

Korean Books Sought by Chinese Readers

VOL.24

2020.07 -

K-Sports

VOL.24

2020.07 -

Publication Industry’s Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic

VOL.24

2020.07 -

Current Status of the Korean Standard Publishing Distribution Data Hub System (BookNet Korea)

VOL.37

2021.08 -

BookTuber’s Pick: A Book-to-Read During Summer Vacation

VOL.37

2021.08 -

Dangjin, Chungcheongnam-do

VOL.37

2021.08 -

Korean Books Loved by German Readers

VOL.37

2021.08 -

Protect the Ecosystem and Environment with Books

VOL.37

2021.08 -

2021 Seoul International Book Fair (SIBF)

VOL.37

2021.08 -

Online Business Meeting for the Copyright Import of K-Books

VOL.25

2020.08 -

Current status of each field in the Korean publishing market ⑦ Publication of practical books for home

VOL.25

2020.08 -

Sokcho, Gangwondo Province

VOL.25

2020.08 -

Popular Books in the Overseas Market: Second Half of 2020

VOL.25

2020.08 -

K-Movie

VOL.25

2020.08 -

Books with Discourses on the Post-COVID-19 Era in Korea

VOL.25

2020.08 -

The publications magazines of Korea

VOL.26

2020.09 -

Current status of each field in the Korean publishing market ⑧ Publication of practical books for social activities

VOL.26

2020.09 -

Book-Stay, a Romantic Night with Books

VOL.26

2020.09 -

Second half of 2020 looks promising for Korean publishing industry

VOL.26

2020.09 -

K-Food

VOL.26

2020.09 -

Domestic Exhibition of Korean books for children & teenagers for the 2020 Moscow International Book Fair

VOL.26

2020.09 -

2018 Publication Industry Factual Survey

VOL.27

2020.10 -

Current status of each field in the Korean publishing market ⑨ Publication of Comics and Art

VOL.27

2020.10 -

Jeju Island

VOL.27

2020.10 -

Korea’s Non-Fiction Books Building Global Competitiveness

VOL.27

2020.10 -

K-Beauty

VOL.27

2020.10 -

Background and Prospect of General Revision of Copyright Law in Korea

VOL.27

2020.10 -

Book Funds and Publication

VOL.36

2021.07 -

BookTuber’s Pick: A Book to Chill Your Summer

VOL.36

2021.07 -

Gimpo, Gyeonggi-do

VOL.36

2021.07 -

The Korean Book Importing Success Story of Diamond, a Japanese Publisher

VOL.36

2021.07 -

A Summer Trip with Books

VOL.36

2021.07 -

Naver and Kakao Compete Over Acquisition of Web-novel and Webtoon Platforms

VOL.36

2021.07 -

K-Book Copyright Fair Online

VOL.28

2020.11 -

Current status of each field in the Korean publishing market ⑩ Publication of Exam and College Books

VOL.28

2020.11 -

Uijeongbu

VOL.28

2020.11 -

Korean Children’s Books Going Global

VOL.28

2020.11 -

K-MUSIC

VOL.28

2020.11 -

How to Live in the Generation where You “Watch” Books

VOL.28

2020.11 -

Publication-Related Organizations in Korea

VOL.29

2020.12 -

Current status of each field in the Korean publishing market ⑪ Educational Publications (textbooks/reference books/home-study materials)

VOL.29

2020.12 -

Suncheon, Jeollanam-do

VOL.29

2020.12 -

Korean Literature in the European Publishing Market

VOL.29

2020.12 -

K-DRAMA

VOL.29

2020.12 -

Seoul International Book Fair 2020

VOL.29

2020.12 -

Overseas Publication Grants

VOL.30

2021.01 -

Current status of each field in the Korean publishing market ⑫ Publications of Children’s Books/Teenage Books

VOL.30

2021.01 -

Bucheon, Gyeonggi-do

VOL.30

2021.01 -

Performance Summary of Korean Publications in the Global Publishing Market in 2020 and Prospects for 2021

VOL.30

2021.01 -

K-WEBTOON & WEBNOVEL

VOL.30

2021.01 -

Status of the Korean Publishing Industry in 2020 and Outlook for 2021

VOL.30

2021.01 -

Tax & Accounting Issues in Korea’s Publishing Industry

VOL.31

2021.02 -

Korea’s Training Programs for Publishers Today and Tomorrow

VOL.31

2021.02 -

Haebangchon, Yongsan-gu, Seoul

VOL.31

2021.02 -

Export Cases of Language Books Developed in Korea

VOL.31

2021.02 -

K-Clothes Culture

VOL.31

2021.02 -

Bestseller Keyword - Money

VOL.31

2021.02 -

Bookstores that Create Books and Culture

VOL.32

2021.03 -

Introducing Korean Sci-Fi!

VOL.32

2021.03 -

K-Education

VOL.32

2021.03 -

Korea’s Audiobook Industry Ready to Fly in 2021

VOL.32

2021.03 -

Major Affairs in Korean Publishing Policy in 2021

VOL.32

2021.03 -

Cases of education materials developed and distributed for overseas Korean learners

VOL.32

2021.03 -

Bookstore Manager’s Pick: Books for Teens

VOL.35

2021.06 -

Daegu, Gyeongsangbuk-do

VOL.33

2021.04 -

Bookkeeper’s Choice - Picture Book

VOL.33

2021.04 -

K-Thriller

VOL.33

2021.04 -

Audiobooks in Korea: Users and Service Providers

VOL.33

2021.04 -

Popular Korean Webtoons in the US

VOL.33

2021.04 -

The “Contactless” Marketing Trend in the Era of COVID-19

VOL.33

2021.04 -

K-Book Promotion Grants Offered by KPIPA & LTI

VOL.33

2021.04 -

The Rise of Literary Agencies

VOL.35

2021.06 -

The Translation Academy of the LTI

VOL.35

2021.06 -

Ganghwa-gun, Incheon Metropolitan City

VOL.35

2021.06 -

Best Import Cases of Jiangsu Phoenix Education Publishing

VOL.35

2021.06 -

Picture Books with Lyrics

VOL.35

2021.06 -

Discussing the Current Status of Korean Picture Books

VOL.35

2021.06 -

The Standard Contracts for Publications

VOL.34

2021.05 -

Audiobooks: Issues and Future Developments

VOL.34

2021.05 -

National Library of Korea(NLK)’s Pick: Essay

VOL.34

2021.05 -

Subscription Models of Local Bookstores

VOL.34

2021.05 -

Kanki Publishing’s Successful Import Cases of Korean Books

VOL.34

2021.05 -

Books Written by Koreans Born and Living Overseas

VOL.34

2021.05 -

Best Book Designs From All Over The World

VOL.34

2021.05